Your cart is currently empty!

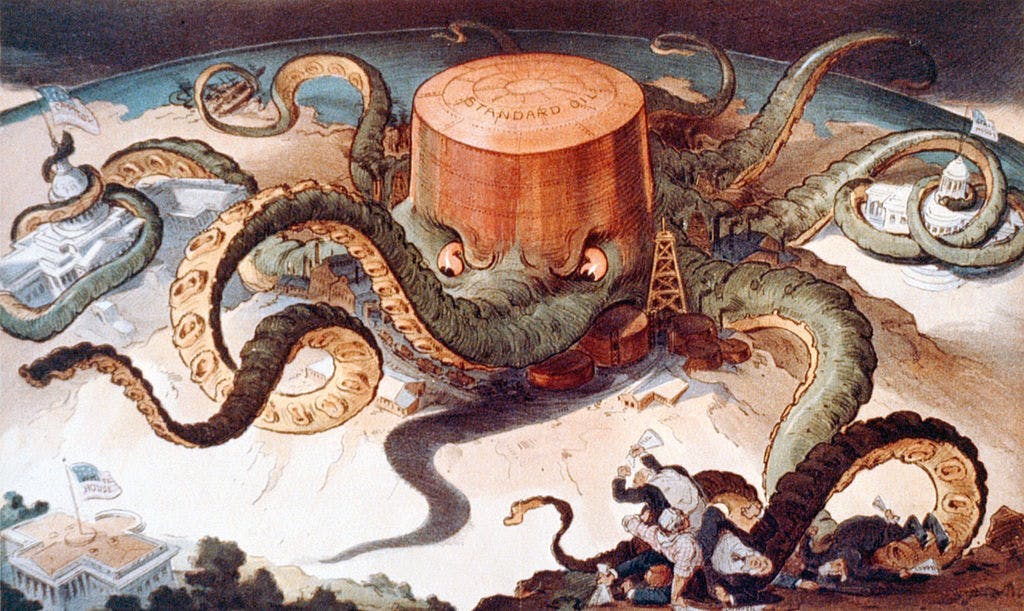

The Google Antitrust Suit

The U.S. government has sued Google for antitrust violations, ending the suspense over which Big Tech company they would take action against first.

The Economist suggests that four lenses should be used to interpret the issues in the Google anti-trust suit, as well as in the other such suits (against Facebook, for example) that might be on the horizon:

- harm

- dominance

- remedies

- delay

“At stake,” they say, “is who controls the rules of public speech.”

Where’s the harm?

Some say that there is political censorship going on, but there is no actual evidence for that claim.

Others hold that Google (and the other Big Tech targets) are not being vigilant enough about false information, but there’s uncertainty over whether a private company should have control over public speech.

If either or both of these claims were true, they would certainly be in conflict with each other. How can one company reasonably be accused of both censoring content and failing to control content?

The vague and contradictory nature of these complaints has led to some vague and contradictory reporting.

The Department of Justice, however, is not squeamish. They used this headline for their announcement of their decision: “Justice Department Sues Monopolist Google For Violating Antitrust Laws.”

The DOJ says that Google pays to have its search engine installed as the default search engine in computers and phones, thus making it very hard for other search engines to compete. I’ve had computers with Bing installed as the default search engine, and was able to change those settings easily. I was also, in a thought experiment a few minutes ago, able to think of four competing search engines and to find all of them (with the help of Google) in my browser.

It’s hard to see that as a monopoly. It’s also hard to see any harm being done to consumers in this situation. Google may have a lot of data, but that’s not covered by antitrust laws.

Dominance

Google certainly dominates search. They have 86.86% of global market share. The fact that there are plenty of other search engines in existence doesn’t limit their control over online search. However, just having dominance is not illegal. As Carl Shapiro says in The Journal of Economic Perspectives, “it would be illogical to urge companies to compete and then tell them they have broken the law when they do so successfully.” Google has dominant market share for search because they have the best search engine.

Google says that’s the people’s choice. People don’t have to use any search engine, and they have plenty of options. Can Google help it if it’s the best?

Google also points out that it doesn’t charge for its search engine and that people using the search function aren’t really Google’s customers. Google’s customers are mostly advertisers.

But Congress created a report which said that there is no real alternative to Google… not in its function as a search engine serving people looking for information, but in its function of sending traffic to websites. Certainly, most business and professional websites do rely on Google to send traffic. We cooperate with Google to get that effect.

And we’re certainly not going to block Google’s bots. Start-up search engines, Congress thought, might get blocked. And it would be hard for them to enter the market effectively when Google has so much data. In fact, it’s hard for them to produce any kind of search engine with limited data. Google’s control over vast amounts of information (including how you behave when visiting a given website) is what makes its algorithm so useful.

Remedies

Back in the heyday of trustbusting, companies did things that were clearly harmful to customers and made it nearly impossible for those customers to change to some other provider. For example, a company might move into a market and lower its prices below cost temporarily to drive competitors out of business. Then, having gotten rid of the competition, that company could raise its prices, and consumers would be forced to buy from the monopoly because they had no other choice. Amazon has been accused of this kind of behavior, but Google doesn’t seem to be doing anything of this kind.

Nothing prevents internet users from switching to DuckDuckGo instead of Google. Nothing keeps them from leaving Facebook for MeWe. Nothing prevents you from giving up Starbucks for your local hospital cafeteria, either, but that doesn’t mean you want to do so.

People who go to Facebook to check in with friends and family or to catch up on news won’t find their friends and family, or their community news, at MeWe. And optimizing for DuckDuckGo won’t give your business the same advantages as optimizing for Google. There is an element of competition there, but neither MeWe nor DuckDuckGo can simply improve their recipe and wait for change. For one thing, they have to use Google to get the attention of prospective customers.

So what’s the solution?

The Economist suggests a completely new business model for Big Tech. “One idea is for people to own their data individually or collectively,” they say. “The social networks would become utilities paid a flat fee, while people or collectives earned the rent from advertisers and set the parameters for what was served up to them. At a stroke that would align the gains from advertising with the burden upon the people being advertised to. If users could port their data to another network, the tech firms would have to compete to provide a good service.”

The Economist recognizes that this would not be a quick fix. And it’s important that the remedy not be worse than the current harm. Senator Elizabeth Warren wants to see Google broken up. She has not been clear on how that would work. Separating Google’s arts and education initiatives from its search would have no clear benefits. Separating its advertising arm from search would clearly be harmful to advertisers — and Google only has about a 30% share in online advertising anyway.

Dividing the search engine among multiple companies, as was done with the phone company, could be done. However, as the Washington Post points out, “Everyone’s searches would probably become less accurate and useful than the ones we’re getting now, because no one company would have enough data to refine those searches as well as Google currently does.”

That certainly would be a solution worse than the current harm.

Delay

Does Google have the power to keep new search engine startups from getting into the market before they run out of money? And, in the context of the current lawsuit, is paying to be the default search engine on new MacBooks the method of creating those delays?

Probably not.

Do your own thought experiment. Imagine you got a new computer today and its default search engine was Ecosia. Will you allow the computer to direct you to Ecosia when you want to search, or will you type in Google.com?

If you simply prefer DuckDuckGo or Bing, will you let the default to Google keep you from using your favorite alternative search engine?

You might go with a default browser, especially if you are one of the millions of people who don’t know what a browser is, but you’ll Google information if you like to Google. If you’d rather Bing it, you can easily find Bing by searching at Google.com.

Google Maps could be another example. Google has, for the first time in human history, mapped the entire world. Would alternative cartography providers have to accomplish that before they could really compete? And if so, does it violate antitrust laws to delay competitors’ entry into the marketplace by doing something absolutely awesome?

As Shapiro points out, “Antitrust cannot solve all manner of economic and social problems and should not be expected to do so.”

by

Tags:

Leave a Reply