Your cart is currently empty!

Native Ads or Tricky Ads?

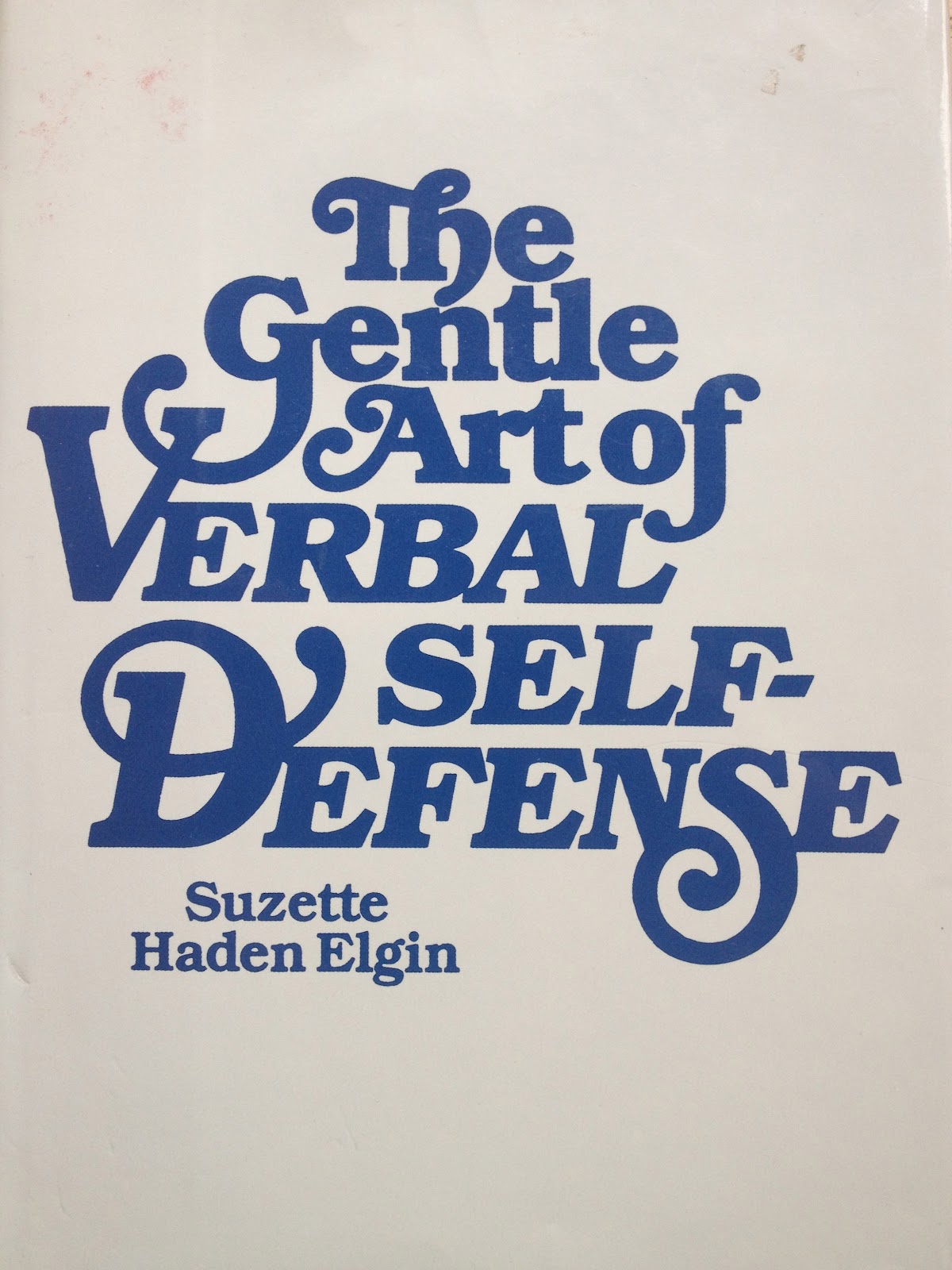

My mother was once paid a useful sum of money to allow a character in Seinfeld to hold one of her books on camera. Now, companies pay to have their products used in TV shows. Product placement on TV might have been the earliest example of what you might now refer to with “native ads,” “sponsored content,” or some other euphemism. It’s now turning up all over the web, at major publishers’ sites as well as on individuals’ blogs.

How useful is this — and how dangerous?

First, let’s be clear on one thing: if you run online ads which cannot be identified as ads, you’re likely to get in trouble. Google has extensive rules for its own ad networks forbidding ads that appear to be news stories, that can’t be distinguished from the background of a website, or which use “trick to click” methods. It will not treat links you’ve paid for as the equivalent of links you’ve earned. The Wall Street Journal and the New York Times have come out strongly on the subject, too, and the FTC held a workshop on it.

Tricking people into thinking that an ad is not an ad is a poor decision.

Yet we know that consumers don’t trust ads as much as they do news, real consumer reviews, or recommendations from people they know — or feel they know. This can include a trusted columnist or a blogger the readers relate to, a celebrity or a respected member of their community. Native ads allow brands to benefit from what looks like editorial content while maintaining control of the message.

This brings up one of the arguments used in favor of sponsored content. Brands claim that they are providing content of the same quality as the unsponsored stuff. If a company commissions a great story or a compelling video, they should — the argument goes — be able to place it just as though it were not paid for by the brand.

Actually, really good ads get plenty of attention. People share commercials they like and talk about ads they enjoy. I shared a commercial last week myself, and you might be able to remember having done so in the past, too. The quality of an ad doesn’t really seem to provide an argument to allow the lines to blur.

Another argument is that bloggers demand to be paid. Getting that word of mouth effect with influential bloggers in some spaces can be difficult if you’re not willing to pay for sponsorship. This may be a good reason to pay for sponsored content. If you pay, you should make sure that it’s clear to visitors that you’ve paid. The problem with this — and the reason that brands are tempted to overstep the boundaries — is that content that has been bought and paid for is less persuasive. Readers figure that bloggers who have been paid will write good reviews regardless of the quality of the items they’re reviewing. Some readers are aware that sponsored posts may actually be written by the brand being “reviewed” and that they all involve some degree of control by the brand.

Bloggers who provide sponsored content, by the way, claim that it is only fair that they should be rewarded for their effort, and that there is no difference between receiving products from a company for review (which I and plenty of mainstream journalists do) and being paid by a brand for a review (which I and mainstream journalists would never do).

Those who argue against the use of native ads, even when they are identified by a disclaimer, point out that people are sometimes deceived by these ads. When they realize that they’ve been taken in, readers’ trust in the brand and the publisher may be lessened. Some fear that increasing use of native ads may devalue online content and limit its usefulness. They point to Nielsen’s studies showing that the internet is currently a more trusted source of information than broadcast media and worry that we’re giving that up when we skate too close to what Google calls “tricky ads.”

If you’re thinking about using native ads or sponsored content, keep these points in mind:

- Be transparent about it. If you pay for it, it’s an ad. Ads are perfectly respectable; pretending they are not ads is not. Once you have placed an ad, you’re within your rights to say “As seen in Glamour” or whatever it might be if you feel like like it.

- Consider other kinds of content marketing. A strong blog on your website has lots of benefits. Guest posts at other websites expose your great content to new audiences and increase authority. Original content at G+ and other social media sites can also be beneficial. And of course, having an article published in the magazines (digital or print) that your viewers read is great exposure.

- Seek unpaid reviews. Consumers read reviews and, according to a study from Ipsos, some 68% of them agree that their purchase decisions are influenced by those reviews. Seek out your fans and ask them to write reviews, send samples of your product to good reviewers, and accept that you won’t have control over what these reviewers say. Spread the word about positive reviews.

- Monitor the conversation about your brand. If you pay attention, you may find that people are already sharing about your brand. Thank them, share their comments, link to them from your company blog, and reap the benefits of sincere, natural word of mouth. Mix natural editorial content in with your native ads in social media to increase the sponsored content’s value — but don’t cross the line.

Native ads may be worth the risk, but tricky ads certainly aren’t.

by

Tags:

Leave a Reply